David Bell is happiest playing it for laughs.

In a more serious vein however

life for the majority in the mid 1600s was far from fun.

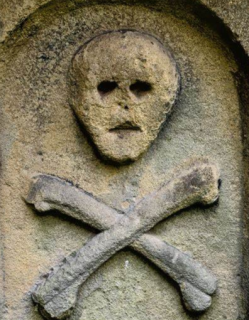

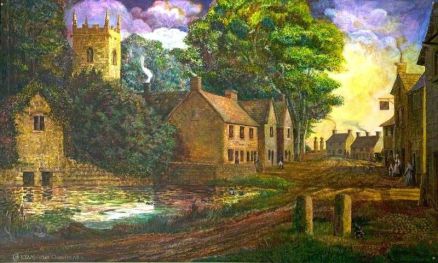

Nestling in the beautiful Peak District, the small village of Eyam lay quietly unaware of what was about to hit it; and propel it into the annals of history for ever. London -160 miles away - existed in the minds of most locals only through talk in the King's Head ale house (now the Miners Arms) with stories from the occasional travelling merchant.The Pestilence as it was known had struck London earlier in 1665; but it was hardly the first epidemic England had experienced. To the villagers of Eyam this may well have looked like one more fanciful tale.

London and Eyam were worlds apart. That is until 350 or so years ago when it is thought that a consignment of second-hand clothing from the City launched the remote Derbyshire village out of its rural slumbers and crashing into a world of horrifying infection.

Eyam's patient zero was a lodger living with the local tailor. In the summer of 1665 the tailor's residence received a delivery from London and within a week or so the lodger was dead. By the end of that year over 40 other villagers had also died.

It is thought that the folds, linings and pockets of the tunics and knickerbockers in the London delivery were infested with plague-carrying fleas and body lice. No science of course existed then to explain such things although a distinct scent of contagion was one of the common signs of plague. Drawing the correct conclusion from what was almost certainly the wrong evidence helped convince Eyam that the disease was likely transmitted through proximity to a pungent smell in the air. Body lice was not suspected.

That winter Eyam’s epidemic seemed to have passed. However - unlike modern day COVID - the onset of warmer weather in the following summer saw a second peak of the dreaded plague return with a vengeance.

By all accounts surrounding areas were unaffected, but how could the spread be halted? In the absence of any regional authority the role of what we now call ‘the science’ was probably taken by the village Church.They would have heard of 'The Plague Orders' already in place in London; and Christianity after all had a track record with plagues: the Bible was full of them.

From the mid-summer of 1666, a full nine months after the first Eyam plague fatality, and with the epidemic now probably at the peak of its second spike, no villagers were to pass beyond boundary stones set half a mile outside the village centre. A type of cordon sanitaire had been belatedly introduced. Provisions were left at the boundary, principally through courtesy of the Earl of Devonshire on the vast neighbouring Chatsworth Estate. Was this a charitable act of concern or one of political self interest ?

The more well-off locals had already long since managed to relocate elsewhere when the outbreak first arrived. Even the resident vicar - with Dominic Cummings like rationale - had dispatched his two small children at the height of the epidemic to relatives in North Yorkshire. But poorer folk probably felt trapped. There was no such thing as being furloughed: those who could do so just had to keep on working as best they could.. Nobody talked of the 'R-number', there was however a belief that if the village could go four or so weeks without a reported plague death, then the pestilence, still believed to be airborne, would have likely evaporated . . . . be spent. They were so close to being right; but they reckoned without fleas and body lice.

Surviving primary evidence does not make it directly clear exactly how the decision to isolate Eyam was made; and formal records say little about how villagers personally viewed their plight having been urged by local church leaders to find strength through God.The god-fearing religious pressures of the day must have been unbelievably stark set against the basic human instinct of self preservation.

Eyam was decimated: 260 villagers died of the plague in just over a year. Estimates of mortality ranged between a third and two-thirds of all the inhabitants. People being kept together would not only have confined the spread but would also have intensified it.

Eyam’s experience does little to help settle today's coronavirus conundrum of ‘herd immunity’ or ‘flattening the curve’. Herd immunity however was arguably what finally ended this epidemic; at a terrible cost it must be said. The village, its survivors immune, could safely come out of their 22 weeks of lockdown . . . . and the rest of the wider region could breath a sigh of relief.

Remarkably Eyam’s dire plight went largely un-heralded for well over a hundred years until it was taken up by moralisers and poets. Today visitors see old chocolate box 'plague cottages' now themed with their modern information plaques, an active church, and even a village museum; leaving all and sundry in no doubt that they are treading in the steps of an immense tragedy. The suffering of 17th century Eyam deservedly attracts reverence, championed enthusiastically by the existing locals who show such collective faith in their ancestor's story.

But fully understanding past times is never easy. The scant primary evidence, the burgeoning subjectivity, the unrelenting God-fearing bias, the motives, the interpretations and the rhetoric . . . . all too easily blur. So I ask you to please pause a while as you digest David Bell's wonderful tongue-in-cheek take on this fascinating period in our history.

I am confident you will agree nonetheless that David's whimsical storytelling style makes for an easy, compelling, and comfortable bed-fellow with life as it was lived all those years ago.

Book an hour of interactive classroom based fun with The Plague Doctor.

Suitably adapted for Key Stage 1 & 2 pupils

When children are laughing . . . . they are learning.

"The Plague Doctor has visited our school five times now.

David generates such positive interaction with his young audience.

The learning opportunities just seem to flow and the children love it "

Liz O'Keefe, Prestbury Junior School, Cheshire

"I never imagined the plague could be such fun.

Our year group were engrossed from beginning to end. Wonderful."

Claire Walsh, Horsforth Newlaithes Junior School, Leeds

Please book early . . . . these sessions are always in high demand

telephone : 01433 639392 email : bell.eyam@sky.com